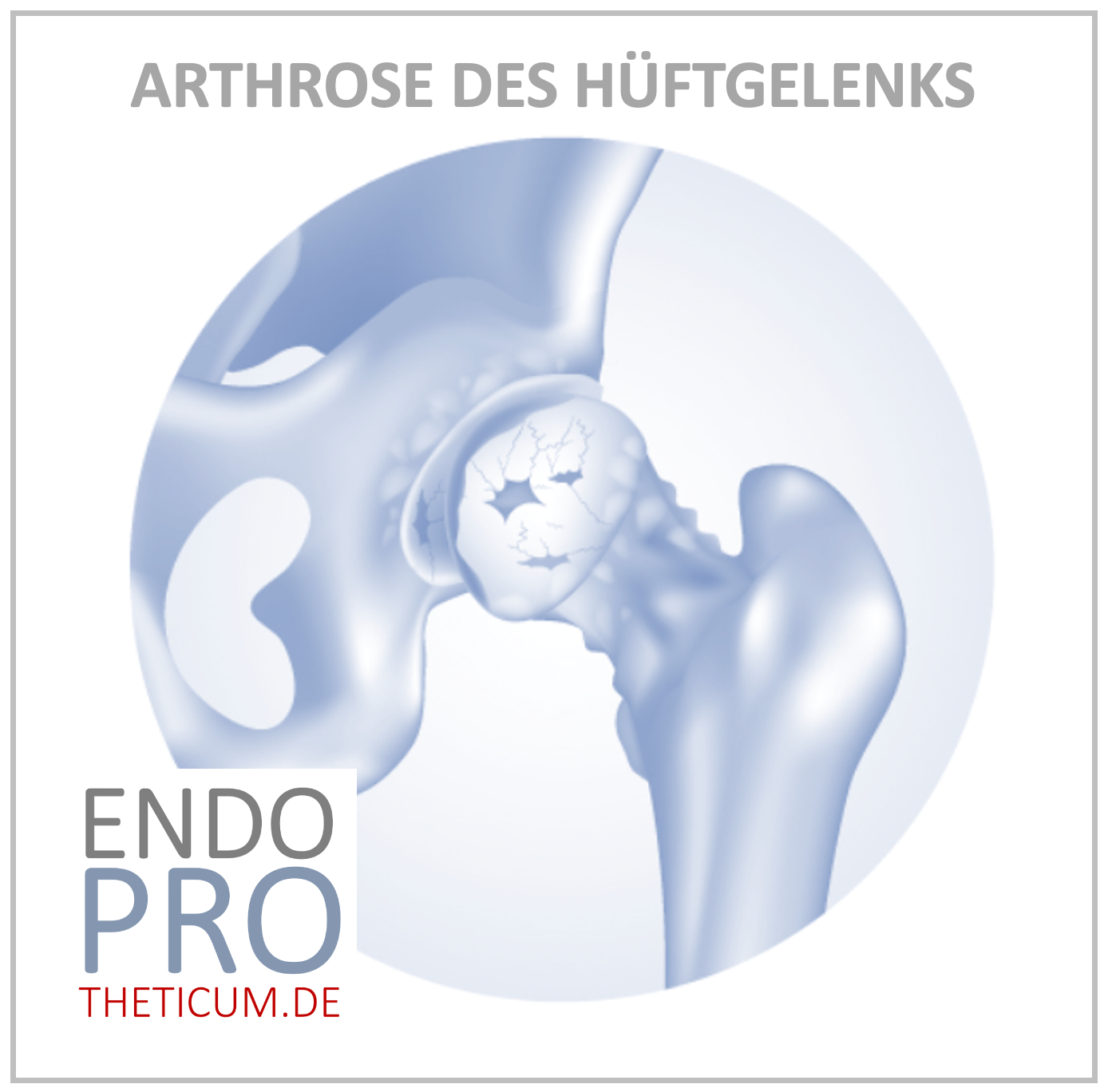

The arthrosis of the hip joint - what happens in the joint?

Understand coxarthrosis - the creeping wear in the hip joint

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is one of the most common chronic degenerative joint diseases of our time – and the hip joint is particularly frequently affected. When patients complain of persistent groin pain, increasing limitations in movement, or a "stiff feeling" in the hip area, the underlying cause is often coxarthrosis – osteoarthritis of the hip joint.

But what exactly happens in the joint? How does it happen that a previously healthy, pain-free hip joint wears down more and more over the years – until it completely loses its function? The disease process is complex and affects not only the cartilage, but also the underlying bone structures, the joint capsule, and even the muscles. Terms like sclerosis , osteophytes , cysts , and joint surface collapse describe the pathological changes that occur during the course of this disease.

In this detailed article, we explain step by step how osteoarthritis of the hip joint develops – from the first cartilage damage to severe coxarthrosis in the end stage. We address the following questions:

- What function does cartilage actually perform in the joint?

- Why does the bone begin to react as cartilage wears down?

- What are sclerosis lesions , how do osteophytes , and what do subchondral cysts ?

- Why does the joint surface collapse – and what does this mean for the everyday lives of those affected?

Anatomy of the hip joint – a perfect interplay

Before we can understand the pathological changes of hip osteoarthritis , it is important to know the normal anatomy of the hip joint. Only by understanding how a healthy joint functions can we comprehend what goes wrong in osteoarthritis .

The hip joint – structure and function

The hip joint is a so-called ball-and-socket joint . It consists of two central bony components:

- the femoral head (caput femoris), the spherical upper part of the thigh bone (femur)

- the hip socket (acetabulum), a semicircular part of the pelvic bone (pelvis)

The femoral head sits like a ball in the socket of the pelvis. Both structures are covered with smooth, white articular cartilage – a layer of hyaline cartilage tissue only a few millimeters thick. This cartilage layer has a crucial protective function.

🧠 The role of articular cartilage – protection, lubrication, shock absorption

The articular cartilage fulfills several vital functions in the hip joint:

- Shock absorption : With every step, enormous forces act on the hip joint – three to five times the body weight. The cartilage distributes these forces evenly and prevents pressure peaks on the underlying bone.

- Minimal friction : Thanks to its smooth surface, the cartilage allows the femoral head and socket to glide almost frictionlessly.

- Protection of the bone layer : The cartilage acts as a natural buffer between the bone surfaces and prevents direct bone contact.

The articular cartilage itself has no blood supply . It receives its nutrients exclusively through the synovial fluid is produced joint capsule , regular, joint-friendly activity crucial for maintaining cartilage health.

What makes cartilage so special – and so vulnerable?

The hyaline cartilage consists of:

- Chondrocytes (cartilage cells)

- Water (70–80% of cartilage mass)

- Type II collagen fibers (for tensile strength)

- Proteoglycans (for elasticity and water retention)

This complex matrix gives cartilage elasticity and compressive strength – a unique combination in the human body. At the same time, however, this also means that if the cartilage is damaged, it can hardly regenerate osteoarthritis over the years .

⚠️ Early cartilage damage often goes unnoticed for a long time

Since cartilage not sensitive to pain , the early stages of osteoarthritis are usually symptom-free . Only when the cartilage has deteriorated to such an extent that the underlying bone reacts – with sclerosis, osteophytes, and cyst formation – do pain, stiffness, and restricted movement occur.

Summary – Anatomy & Cartilage Overview

femoral head:

It bears the body weight, forms the movable sphere

Hip socket:

Fixed mounting in the pelvis, guides and stabilizes

Articular cartilage:

Shock absorber, sliding surface, protection against bone contact

Synovial fluid:

Cartilage nutrition, friction reduction

→ Even minor damage to the cartilage can coxarthrosis .

What happens in the hip joint during osteoarthritis? – Understanding coxarthrosis

Osteoarthritis of the hip joint , medically known as coxarthrosis , describes a gradual wear-and-tear process that progresses through several stages . It is a degenerative joint disease in which the cartilage – the natural protective layer over the bone – is progressively destroyed. But osteoarthritis is much more than "just" cartilage loss: the bone, the joint capsule, the synovial fluid, and the surrounding structures also change – and as the disease progresses, this leads to significant limitations in everyday life.

🧩 What is the difference between osteoarthritis and arthritis?

Before we delve deeper, it is important osteoarthritis arthritis, which is often confused with it :

Term/Definition: Osteoarthritis: Degenerative, wear-related breakdown of cartilage and joint structures; Arthritis: Inflammatory joint disease (e.g., rheumatism, infection, gout)

→ While osteoarthritis is primarily characterized by wear and tear, arthritis is dominated by an inflammatory response . However, in the later stages of coxarthrosis, secondary inflammation occur due to worn cartilage and joint irritation – this is then referred to as activated osteoarthritis.

🔎 Primary and secondary coxarthrosis – what are the causes?

The causes of osteoarthritis in the hip joint are multifaceted. A basic distinction is made between primary and secondary coxarthrosis :

🟡 Primary coxarthrosis

- Cause unknown (idiopathic)

- It usually occurs from the age of 50 onwards

- Probably age-related degeneration, genetic factors, reduced regenerative capacity

🔴 Secondary coxarthrosis

- Clear triggering factors are present:

- Hip dysplasia (congenital malformation of the hip socket)

- Perthes disease , slipped capital femoral epiphysis (growth disorders)

- Injuries (e.g., femoral head fracture, dislocation)

- Overweight , leg length discrepancies , incorrect loading

- Rheumatic diseases or avascular necrosis of the femoral head

→ In both cases, the process results in a common endpoint: increasing destruction of the articular cartilage with reactions of the underlying bone .

🧬 What risk factors promote osteoarthritis of the hip?

The development of hip osteoarthritis is promoted by various risk factors:

- Age : The regenerative capacity of cartilage decreases with increasing age.

- Genetics : Familial clustering suggests hereditary factors.

- Excess weight : Significantly increases the mechanical pressure on the hip joint.

- Malpositions : e.g., X- or O-leg position, hip dysplasia

- Occupational strain : Long-term lifting of heavy loads or working in a deep squatting position

- Sports with high impact load : e.g., football, marathon running

→ The combination of several factors significantly increases the risk.

🧠 What happens first in osteoarthritis of the hip joint? – The onset in the cartilage

, microscopic changes appear – without any clinical symptoms. The cartilage layer initially loses water content, which reduces its elasticity. As a result, the mechanical stresses in the joint can no longer be adequately cushioned .

🔬 The first changes:

- Reduction of proteoglycans

- Cellular changes in chondrocytes

- Roughening of the cartilage surface (fibrillation)

- Microcracks and fissures within the cartilage tissue

- Locally progressive thinning

These processes lead to a disruption of the biomechanical balance wear down in certain areas , especially under unilateral stress – for example, in the area of the acetabular roof (superolateral).

📉 How wear and tear continues to develop – a vicious cycle

As cartilage deteriorates, the entire joint system becomes unbalanced. This creates a cycle of:

- Mechanical overload

- Cartilage degeneration

- Joint inflammation (activated osteoarthritis)

- Bone reaction (sclerosis, osteophytes, cysts)

The cartilage debris irritates the synovial membrane, leading to synovitis – an inflammation of the joint capsule. This causes the capsule to produce increased and altered synovial fluid, further accelerating cartilage degradation. The joint's gliding ability decreases, and pain develops – initially only during activity, but later also at rest.

🦴 What happens to the bone beneath the cartilage? – The beginning of the remodeling processes

As the cartilage becomes increasingly thin, the underlying bone is eventually exposed to direct stress – without any cushioning. The body reacts to this with:

- Hardening and thickening of the bone = sclerosis

- Formation of bone outgrowths = osteophytes

- Formation of cavities in the bone = cysts

These changes are the first visible signs of advanced coxarthrosis in an X-ray image – even if the patient is not yet experiencing any pronounced symptoms.

The stages of coxarthrosis – From the first cartilage damage to the collapse of the joint surface

( coxarthrosis ) typically progresses through several clearly defined stages . These stages are characterized by progressive changes in the cartilage and bone. The bone's reaction to cartilage wear is particularly crucial, as it leads to sclerosis , osteophyte formation , cyst formation , and ultimately, joint surface collapse .

The following section describes in detail the four typical stages of coxarthrosis with all their characteristic features and structural changes.

🔹 Stage I – Early stage: The beginning of cartilage damage

In the first stage, microscopically fine changes are visible in the cartilage tissue. Radiologically, coxarthrosis is usually not yet visible or can only be recognized as minimal narrowing of the joint space .

Changes in the joint:

- The cartilage loses water and becomes more brittle.

- The lubricity decreases.

- Initial roughening of the cartilage surface (fibrillation).

- Partial synovial irritation with incipient joint inflammation.

Symptoms:

- Usually no or only minor complaints.

- Morning stiffness.

- Pain after exertion (e.g., prolonged walking, standing).

Important: biomechanical disorder already exists , which accelerates the further progression.

🔹 Stage II – Advanced Stage: Beginning of bone reactions

At this stage, the body begins to react to the increasing cartilage wear and the lack of cushioning provided by cartilage tissue. This leads to structural remodeling processes in the subchondral bone.

✅ Sclerosis: The bone's first response

Sclerosis is a hardening and thickening of the subchondral bone directly below the damaged cartilage surface.

Why does sclerosis develop?

- Due to the lack of cushioning, mechanical stresses act directly on the bone.

- The bone reacts to this with increased calcium deposition and remodeling in order to withstand the increased load.

- The dense bone structure appears in the X-ray image as a bright line under the cartilage (subchondral sclerosis).

The consequence: The bone becomes stronger but less elastic – which further impairs shock absorption. Furthermore, sclerosis increases the risk of subsequent cyst formation.

✅ Osteophytes: The attempt to enlarge joint surfaces

Osteophytes are bony growths at the edge of a joint that develop when the body tries to distribute the load over a larger area.

Protective function:

- Enlargement of the joint surface.

- Load distribution in unstable joint mechanics.

Problem:

- Osteophytes often grow so large that they restrict mobility.

- They can press into soft tissues or adjacent structures (e.g., joint capsule, nerves) and cause pain there.

✅ Joint space narrowing:

- The joint space appears increasingly narrow in the X-ray image.

- Signs of reduced or missing cartilage.

Symptoms:

- Increasing pain during exertion.

- Initial limitations in movement.

- Start-up pain, stiffness.

🔹 Stage III – Late stage: Cyst formation and structural instability

In the third stage, osteoarthritis of the hip has progressed significantly. The cartilage surface is severely degraded, and the bone continues to react. This results in the formation of so-called subchondral cysts – fluid-filled cavities within the bone.

✅ How do cysts develop?

- Sclerosis leads to a shielding of the load.

- Pressure peaks are concentrated in narrowly defined areas.

- Micro-tears and tiny hemorrhages lead to the formation of cysts.

Graves cysts:

- Mostly in the area of the femoral head and/or the acetabulum.

- Clearly visible in X-ray or MRI scans.

- They can merge together and form large cavities.

Consequence:

- The bone loses its load-bearing capacity.

- Risk of microfractures.

- Severe pain upon exertion.

Symptoms:

- Severe pain even at rest.

- Severe limitations in movement.

- Muscle tension, gait disturbances.

🔹 Stage IV – Final stage: Collapse of the articular surface

In the final stage, the cartilage is completely broken down. The bone structure, riddled with cysts, loses its stability – and the joint surface collapses .

✅ What happens during a break-in?

- The bone plate that supports the joint collapses.

- The hip joint becomes unstable.

- The contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum becomes deformed.

Consequences:

- Sudden worsening of pain.

- Massive loss of mobility.

- Inflammatory reactions, protective posture, muscular imbalance.

Therapeutic consequence:

- At this stage, conservative therapies are no longer effective.

- An artificial hip joint (endoprosthesis) will be necessary.

How cartilage deteriorates – the cascade begins

The importance of cartilage in the hip joint

The cartilage in the hip joint is a smooth, elastic layer that covers the femoral head and the acetabulum. It acts as a natural shock absorber and gliding surface , minimizing friction between the bones and allowing for even load distribution. Cartilage consists primarily of water, collagen fibers, and proteoglycans – molecules that bind water and provide elasticity.

Initial damage to the cartilage – micro-damage and mechanical stress

Overuse, misalignment, or aging processes initially cause tiny micro-tears . These lead to impaired structure and function. The cartilage gradually loses its ability to retain water, which significantly reduces its elasticity.

Decrease in proteoglycans and water retention

With degeneration, the proteoglycan in the cartilage decreases. This means the cartilage can bind less water, becomes drier, more brittle, and less elastic. As a result, the cartilage's shock-absorbing function is further diminished, and stress is distributed unevenly to the underlying bone.

Fibrillation, cracks and detachment of the cartilage

fibrillation occurs – the roughening of the cartilage surface. Over time, deeper cracks and abrasions develop. Large portions of the cartilage eventually detach from the bone, creating a direct bone-on-bone contact surface that causes pain and inflammation.

Loss of shock-absorbing function

The loss of the cartilage layer leads to increased stress on the bone, which is now in direct contact with the opposing bone without the protective barrier. This altered pressure distribution is the starting point for subsequent bone reactions, such as sclerosis .

How the bone reacts – sclerosis develops

What does sclerosis mean in the context of coxarthrosis?

In orthopedics, sclerosis describes thickening and hardening of the subchondral bone , that is, the bone located directly beneath the articular cartilage. In the context of hip osteoarthritis – coxarthrosis – sclerosis is a typical reaction of the bone to the increasing stress it is subjected to due to cartilage wear . The term "sclerosis" derives from the Greek "skleros," meaning "hard" – and that is precisely what happens: the bone hardens as a protective measure.

Why does the bone react with sclerosis?

In a healthy hip joint, the hyaline articular cartilage all impact and pressure loads during walking, running, or jumping. This cushioning function protects the underlying bone.

With the onset of cartilage degeneration – due to aging, overuse, or other factors – the cartilage loses its elasticity and thickness. It can no longer adequately distribute the load. As a result, the underlying bone is to increased mechanical stress .

The body reacts to this overload by strengthening the bone : it builds up more bone material to better bear the load. This results in a more compact, denser bone structure – sclerosis.

Consequences of sclerotic changes in the hip joint

At first glance, this reaction seems sensible: the bone becomes stronger to withstand the increasing pressure. However, in the long term, this adaptation brings significant disadvantages :

- Reduced shock absorption : Sclerotic bone is less elastic. This leads to poorer cushioning and increases the stress on the remaining cartilage and adjacent joint areas.

- Pain : The increased bone density is accompanied by heightened sensitivity to pressure. Patients often report deep-seated pain in the groin or buttocks , especially during exertion.

- Promoting further damage : The altered biomechanics in the joint further accelerate the degenerative process. Sclerosis is therefore not only a consequence, but also a contributing factor to the progression of osteoarthritis.

Where does sclerosis typically occur?

In the context of coxarthrosis, sclerotic changes are frequently seen in two areas:

- In the femoral head : The load-bearing areas, which are subjected to pressure with every movement, are particularly affected.

- In the acetabulum (the roof of the hip socket) : Here, too, the load from body weight is greatest, especially in cases of misalignment or asymmetrical loading.

These sclerotic zones are clearly visible on X-rays : The bone appears particularly bright (radiodens) there because it is denser than the surrounding healthy bone.

Significance of sclerosis in the overall course of hip osteoarthritis

Sclerosis represents a crucial turning point in the course of osteoarthritis. It marks the transition from cartilage wear to the active remodeling phase in the bone . Once sclerosis occurs, osteoarthritis is usually in a more advanced stage – and there is an increased risk of developing further degenerative changes such as osteophyte formation, cyst formation, and ultimately, joint surface collapse .

Osteophyte formation – when the bone builds "protective walls"

What are osteophytes?

Osteophytes are bony outgrowths or growths that form at the edges of a joint coxarthrosis reactive remodeling process of the bone in response to chronic stress, instability, or cartilage loss. Colloquially, they are also referred to as "bone spurs" or "bone growths."

How do osteophytes form?

Wear and tear of the articular cartilage means that the load is no longer distributed evenly across the joint surfaces. This leads to mechanical overload at the joint margin. The body reacts to this with an adaptive measure : it attempts to increase the load-bearing areas and distribute the mechanical load more effectively.

This occurs through the formation of new bone material – osteophytes are formed. This process is part of the so-called reactive changes in osteoarthritis and is often an indication of an already advanced stage of the disease.

The purpose behind osteophytes: a protective mechanism with side effects

In the short term, the body pursues one goal with the formation of osteophytes:

- Surface area increase for pressure distribution

- Stabilization of the joint in cases of increasing instability

However, in the long term, osteophytes lead to functional problems :

- Restriction of mobility : The bony growths protrude into the joint space and block normal movements, e.g. when bending or abducting the leg.

- Pain : Significant pain can occur, especially when osteophytes press on surrounding soft tissues such as capsules, tendons, or nerves.

- Inflammation : Mechanical friction can cause local irritation – a so-called "activated osteoarthritis" with swelling, increased warmth and heightened pain sensitivity.

Where do osteophytes typically occur in the hip joint?

In coxarthrosis, osteophytes develop primarily at the following locations:

- On the femoral head (caput femoris) : Especially at the edges of the cartilage that are overloaded.

- At the acetabular rim (labrum acetabulare) : So-called marginal osteophytes often develop here.

- At the transition to the femoral neck : These osteophytes can lead to a narrowing in the joint, which is called impingement.

The location and extent of osteophytes provide the experienced orthopedist with important information about the stage and dynamics of osteoarthritis.

How can osteophytes be identified?

Diagnostic imaging , especially conventional X-rays , is very well suited for detecting osteophytes. They appear as:

- pointed or bulbous protrusions at the joint edge

- Well-defined, radiopaque structures outside the regular joint space

In advanced cases, osteophytes can grow so large that they partially or completely bridge the joint space – a sign of severe coxarthrosis .

Clinical significance of osteophytes

While small osteophytes often cause no symptoms, larger growths can lead to significant limitations. They:

- reduce range of motion

- increase mechanical friction

- promote inflammatory irritations

- They can complicate surgical procedures, e.g., during hip replacement surgery

Therefore, osteophytes are not only a diagnostic feature, but also therapeutically relevant.

Cyst formation – subchondral cysts as a sign of advanced osteoarthritis

What are subchondral cysts?

Subchondral cysts – often also subchondral cysts – are fluid-filled cavities in the bone beneath the articular cartilage. They typically occur in advanced osteoarthritis , particularly in hip osteoarthritis , and are a sign of continued mechanical overload and structural disintegration of the joint.

These cysts are usually located in the subchondral bone , that is, in the area of the bone directly beneath the articular cartilage. Commonly affected locations are the femoral head and the acetabulum (hip socket) .

How do rock cysts form?

The pathogenesis of subchondral cysts is complex and multifactorial. The central mechanisms are:

- Pressure and impact stress due to cartilage loss: The loss of the shock-absorbing cartilage layer increases the stress on the underlying bone. This leads to sclerosis. In the long term, the area beneath this layer experiences reduced stress, as the sclerosis shields it from further impact. Particularly in areas where sclerosis , microcracks occur in the bone tissue.

- Injection of synovial fluid: Through these cracks, synovial fluid penetrate the bone. There it accumulates and forms a fluid-filled cavity – the subchondral cyst.

- Degeneration and breakdown processes: Inflammatory processes and enzymatic changes contribute to further tissue breakdown. The cysts can enlarge and partially fuse together.

- Pressure relief through cyst formation: The body attempts to compensate for the mechanical stress by forming cavities – which, however, undermines the stability of the bone structure in the long term.

Interaction of sclerosis and cyst formation

It is particularly noteworthy that sclerosis and cyst formation often side by side in the same bone area . This initially seems contradictory:

- Sclerosis refers to the thickening and strengthening of the bone structure.

- Cyst formation, on the other hand, means substance loss and the creation of cavities.

In fact, these are complementary processes :

- Sclerosis attempts to buffer the stress .

- Cyst formation occurs when this compensation is no longer sufficient and the bone structurally fails.

The result is an unstable, porous bone structure that increasingly loses its load-bearing capacity.

Symptoms caused by subchondral cysts

Bone cysts do not usually cause isolated symptoms, but exacerbate the overall problem of coxarthrosis:

- Increasing pain , especially during exertion

- Instability of the joint

- Reduction in bone bearing capacity

- Risk of joint surface collapse (Chapter 9)

How can you recognize rock cysts?

Diagnostic imaging is crucial:

- X-ray : shows the cysts as sharply defined, radiolucent (transparent) areas in the bone.

- MRI : even more sensitive – it can also detect smaller cysts and the associated soft tissue changes.

- CT scan : helpful for assessing bone structure and cyst extent

Significance of cysts for the prognosis of hip osteoarthritis

Subchondral cysts are considered a sign that worsens the prognosis in osteoarthritis. Their presence usually indicates:

- an advanced stage of the disease

- high mechanical stress in the joint

- impending collapse of the joint surface

At this stage, the only therapeutic option is often surgical intervention – usually by replacing the hip joint .

The collapse of the joint surface – the fatal endpoint

What happens when the joint surface collapses?

Joint surface collapse is the most severe and final stage of coxarthrosis. It refers to the breakdown of the bone surface in the area of previously formed cysts and sclerotic areas. The loss of load-bearing bone structure and the massive damage to the articular cartilage lead to direct bone-on-bone friction , which is extremely painful and severely restricts the function of the hip joint.

Mechanism of joint surface collapse

- The previously formed subchondral cysts make the bone increasingly porous and unstable.

- the accompanying sclerosis creates a densification in some areas, it cannot compensate for the structural weakness caused by the cysts.

- Under stress, parts of the joint surface collapse, leading to a sudden loss of stability.

- This instability leads to a sudden deterioration of joint function and severe pain.

Consequences of joint surface collapse

- Massive loss of mobility: Patients can barely move their hip joint, walking is severely restricted or impossible.

- Severe pain: Bone rubbing causes persistent and intense pain, often even at rest.

- Gait disturbances: Even simple movements become a torment; often a walker or wheelchair is necessary.

- Secondary changes: Muscle atrophy, compensatory postures and incorrect loading of other joints are the result.

Clinical significance and therapy

A collapse of the joint surface usually means the end of all conservative treatment options. A hip replacement (total hip arthroplasty) is generally unavoidable in order to relieve pain, restore mobility, and significantly improve quality of life.

Summary

- The collapse of the joint surface is the final stage of coxarthrosis.

- It arises from instability resulting from cyst formation and sclerosis.

- Leads to extreme pain and loss of mobility.

- A hip replacement is usually the only permanent solution.

How everyday life changes – symptoms during the course of coxarthrosis

Pain – the central symptom

The progression of hip osteoarthritis is characterized by increasing pain intensity, which typically manifests itself in various forms:

- Start-up pain: At the beginning of strenuous movements, those affected often feel stabbing or pulling pains, which improve again after a short movement.

- Pain on exertion: As osteoarthritis progresses, pain intensifies when walking, climbing stairs, or standing for extended periods.

- Rest pain: In the final stage, pain also occurs at rest or at night, and those affected often suffer from sleep disorders.

Movement restrictions and functional consequences

The mobility of the hip joint decreases further and further due to cartilage loss, osteophytes and cyst formation:

- Difficulty putting on shoes and socks or bending over.

- Problems getting up from a seated position .

- Limited ability to walk or stand for extended periods.

- Stiffness in the morning and after periods of rest.

Protective postures and muscular consequences

To avoid pain, patients often adopt protective postures that relieve the affected leg. However, this leads to:

- Uneven stress on other joints (e.g., knees, spine).

- Muscle wasting (muscle atrophy) in the area of the hip and thigh.

- Increased risk of falls due to reduced stability.

Psychological effects

Chronic pain and limited mobility can lead to:

- frustration and social isolation .

- Depression and anxiety, especially when daily life is severely affected.

- The loss of independence and quality of life.

Diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis (coxarthrosis)

History and clinical examination

The first step in diagnosing coxarthrosis is a detailed medical history, during which the doctor gathers important information:

- Symptoms: Onset, course, character of pain (e.g., start-up pain, pain on exertion)

- Movement restrictions: Which movements are painful or restricted?

- Pre-existing conditions: injuries, surgeries, familial osteoarthritis

During the physical examination, typical signs are checked:

- Range of motion: Limitations in flexion, abduction, and rotation of the hip joint

- Pain trigger: Certain movements or pressure on the joint

- Gait pattern: Limping or shortening of stride length

- Muscle status: Atrophy or weakness of the hip muscles

Imaging procedures

Imaging studies are crucial for the accurate assessment of joint changes.

roentgen

- Standard procedures for diagnostic confirmation

- Typical findings in coxarthrosis:

- Narrowing of the joint space due to cartilage loss

- Sclerosis in the subchondral bone of the femoral head and acetabulum

- Osteophyte formation at the joint margin

- Subchondral cysts as radiolucent areas

- It also helps with the staging of osteoarthritis

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- More sensitive than X-rays, especially in early stages

- Visualization of cartilage defects, soft tissue changes and joint effusion

- Visualization of cysts and bone marrow edema

Computed tomography (CT)

- In addition to the assessment of bone structure

- Helpful for complex deformities or before operations

Laboratory tests

- In osteoarthritis, no specific laboratory values are elevated.

- To differentiate between inflammatory joint diseases, inflammatory parameters (e.g. CRP, ESR) can be determined.

Diagnosis confirmation and staging

A diagnosis of coxarthrosis can be made with a high degree of certainty through a combination of medical history, clinical examination, and imaging. Staging (e.g., according to Kellgren and Lawrence) is based on the X-ray findings and is important for treatment planning.

Treatment options for hip osteoarthritis

Conservative therapy

In the early and middle stages of coxarthrosis, conservative treatment is the primary focus in order to relieve pain, maintain mobility and slow the progression of the disease.

Painkillers

- NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen or diclofenac for pain relief and inflammation reduction.

- Paracetamol as an alternative in case of contraindications.

- Topical analgesics (e.g. pain patches or gels) for local application.

physical therapy

- Strengthening the muscles around the hip joint for stabilization.

- Improvement of mobility and joint function.

- Training in joint-friendly movement patterns.

Weight loss

- Reduces the strain on the hip joint and slows down cartilage degeneration.

Injection therapies

- Hyaluronic acid injections: Improved joint lubrication.

- Cortisone injections: Short-term anti-inflammatory and pain reduction.

When do conservative measures no longer help?

- In cases of advanced coxarthrosis with significant joint surface collapse, severe pain at rest and massively restricted mobility.

- When quality of life suffers greatly and everyday activities are hardly possible anymore.

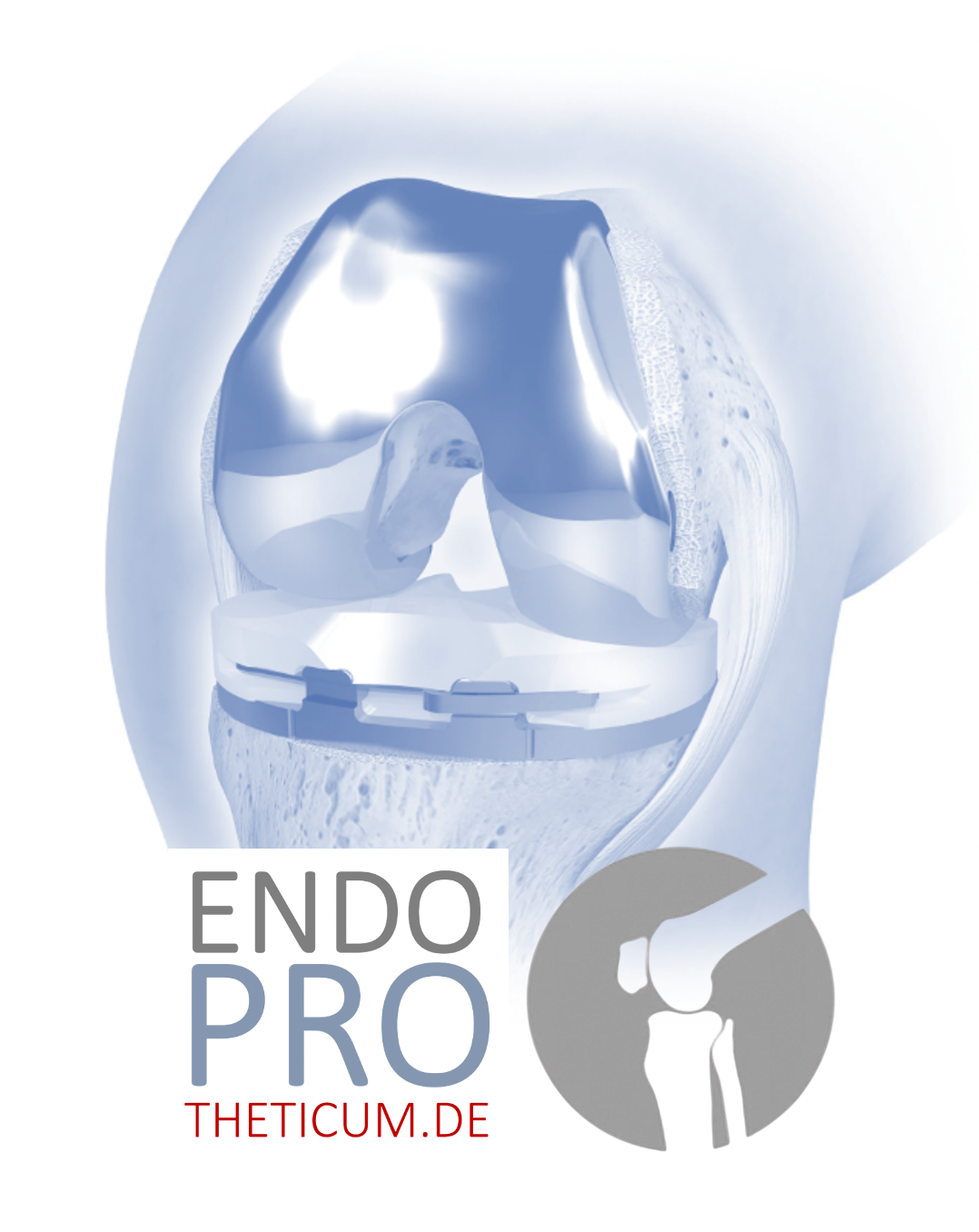

Surgical treatment: Hip replacement (total hip arthroplasty)

Hip replacement is the proven therapy in the end stage of coxarthrosis and is used when conservative measures are no longer sufficient.

The goal of hip replacement

- Freedom from pain or significant pain relief.

- Restoration of mobility and function.

- Improvement of quality of life and mobility.

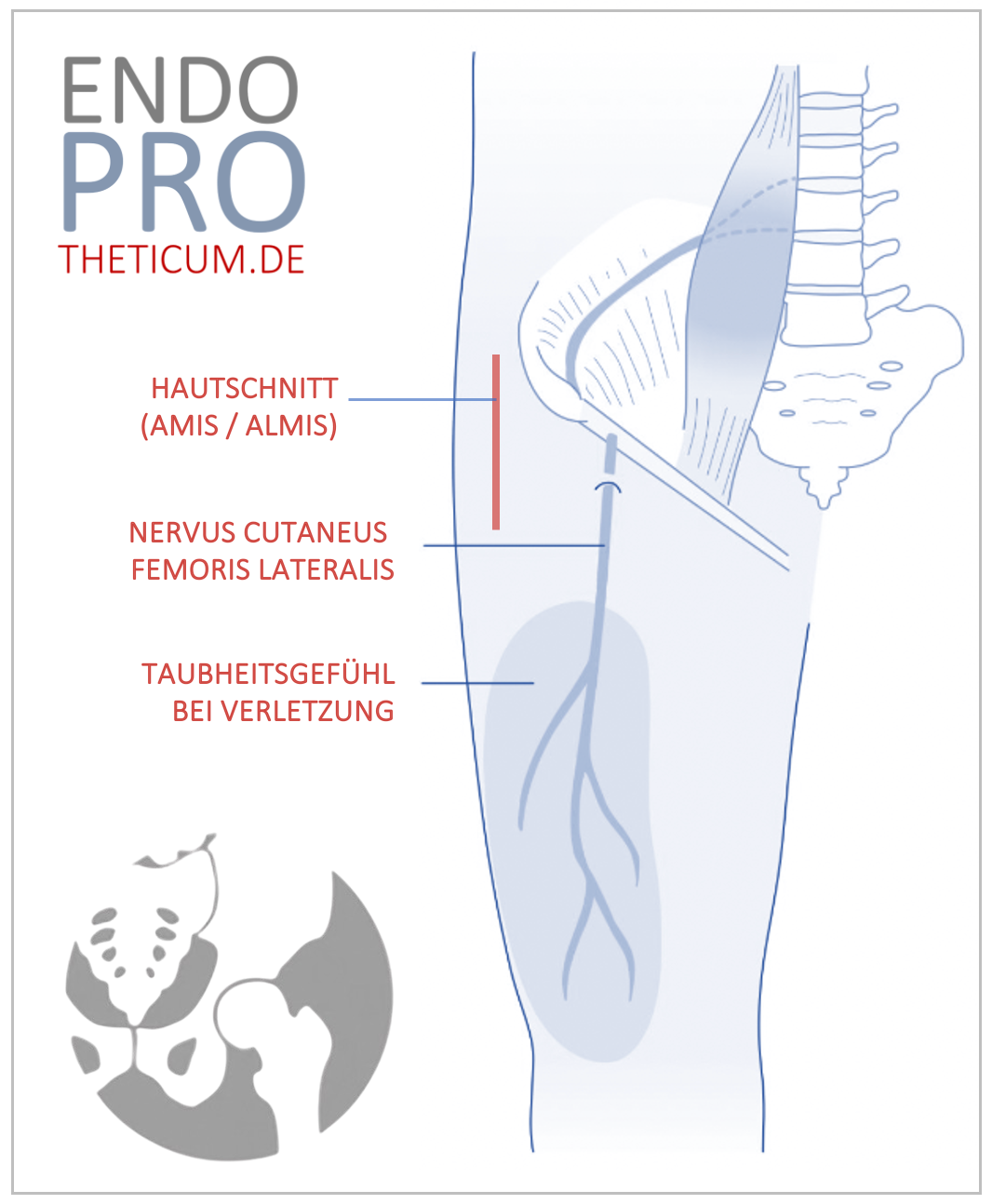

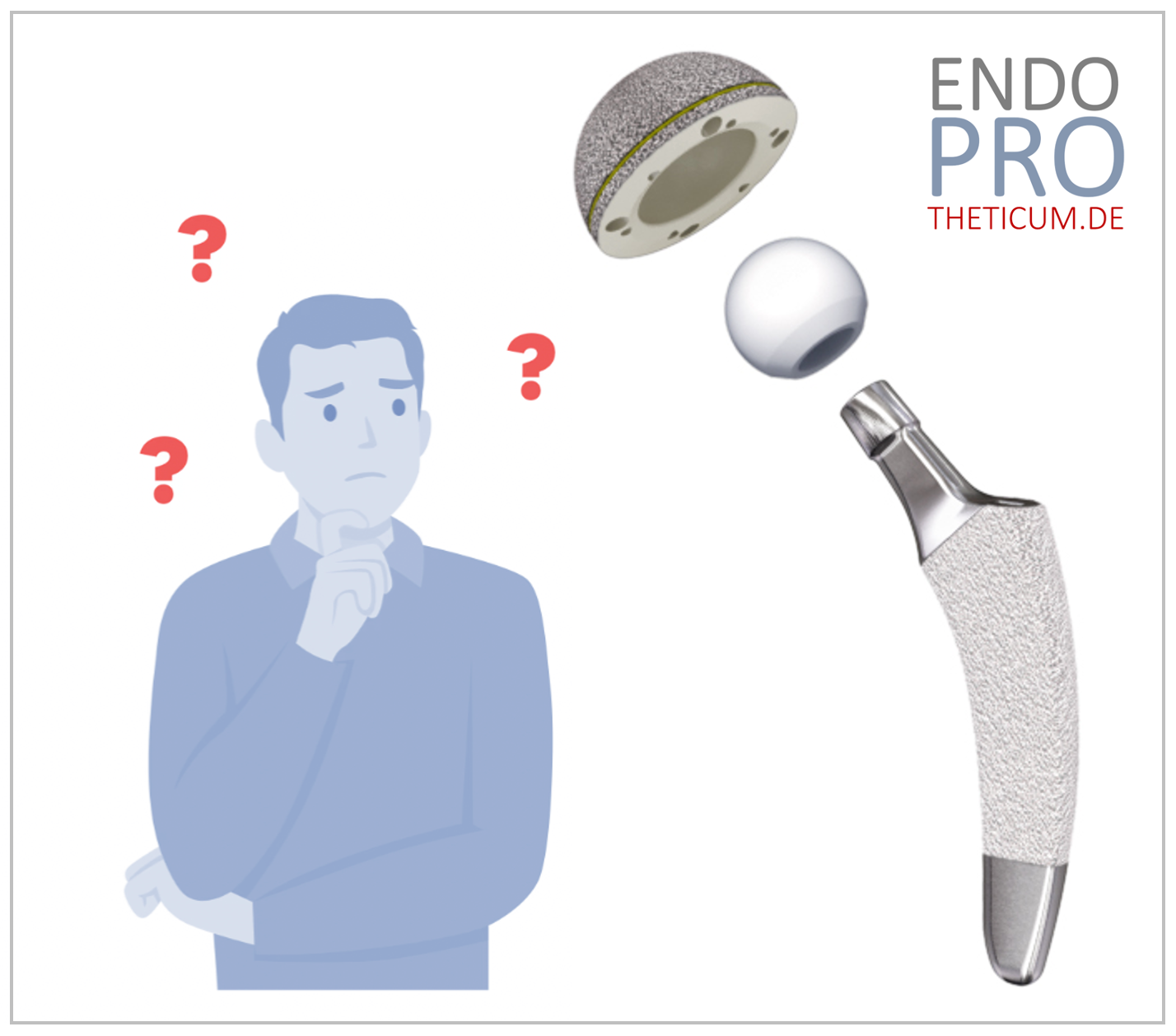

Surgery and prosthesis types

- Different types of prostheses (cemented, cementless, hybrid) depending on the patient and bone quality.

- Minimally invasive approaches to protect soft tissues.

- Individual adaptation to anatomical conditions.

Post-treatment

- Early mobilization and physiotherapy.

- Monitoring of wound healing and prosthesis position.

- Long-term follow-up care to ensure function.

Treatment for hip osteoarthritis is individualized and depends on the stage of the disease and the symptoms. Modern hip replacements now allow for a quick and lasting return to an active life.

Conclusion

What happens in the joint during coxarthrosis?

Osteoarthritis of the hip joint, also coxarthrosis , is a complex degenerative process that begins with the progressive wear and tear of the protective cartilage. In a healthy joint, this cartilage serves as an elastic gliding layer that protects the bones from direct contact and cushions impacts.

Over time, mechanical overload, micro-injuries, and biological changes lead to a gradual breakdown of cartilage. In this process, the cartilage loses its ability to retain water and its elasticity, resulting in cracks and eventually exposed bone surfaces.

The bone reacts to the lack of cushioning by thickening, a condition known as sclerosis , primarily in the femoral head and acetabulum. Additionally, osteophytes as bony outgrowths at the joint margin. While these increase the joint surface area and distribute pressure, they ultimately lead to restricted movement.

The increased stress causes small cavities to form in the bone, known as subchondral cysts or bone cysts . These are an indication of increasing instability and structural weakness.

In the final stage, the joint surface collapses at the cystic sites, leading to a sudden and massive deterioration with severe pain, loss of mobility, and impaired function. At this stage, hip replacement surgery unavoidable to restore quality of life.

The further the disease progresses, the more limited the treatment options become without surgery.

Modern medicine and opportunities

Thanks to modern diagnostics and innovative surgical methods, endoprosthetics now enables many affected individuals to experience a significant improvement in their quality of life and mobility.

Individual and professional care by experienced specialists, such as that offered ENDOPROTHETICUM Mainz

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT?

You are welcome to make an appointment either by phone or online .